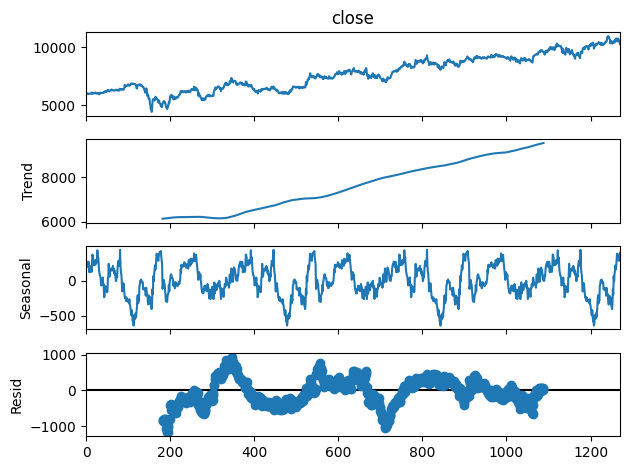

Seasonal Decompose

Seasonal decomposition is a powerful method for breaking down stock price data into its fundamental components, revealing underlying patterns that may not be immediately visible. The technique divides the time series data into three main components:- Trend: This component captures the long-term movement in the data, showing the general direction (upward, downward, or stable) in stock prices over time. The trend can highlight market sentiment and provide insights into sustained patterns that might be associated with company performance or broader economic indicators.

- Seasonal: The seasonal component reflects recurring fluctuations or cycles in the data, often influenced by periodic events like earnings announcements, fiscal quarters, or even broader economic cycles. Analyzing seasonality allows us to understand recurring behaviors in stock price movements and anticipate potential cyclic trends.

- Residual: Also known as the “remainder” or “noise,” this component captures random fluctuations and irregularities in the data that aren’t explained by trend or seasonality. These variations can result from unexpected events, news releases, or other market anomalies.

Additive vs. Multiplicative Decomposition

When performing seasonal decomposition, it’s essential to understand the distinction between additive and multiplicative models. These two models define how the components (trend, seasonal, and residual) interact within the time series data.-

Additive Model: In an additive model, the components are added together to reconstruct the original time series. This model assumes that the effect of each component is constant over time. It’s most suitable when variations in seasonality and residuals are relatively uniform.

- Formula:

Y(t) = Trend(t) + Seasonal(t) + Residual(t)

- Formula:

-

Multiplicative Model: In a multiplicative model, the components are multiplied to recreate the time series. This model is typically used when the seasonal variations or noise increase or decrease proportionally with the level of the trend. This approach is effective when the amplitude of seasonal effects grows with stock price changes.

- Formula:

Y(t) = Trend(t) * Seasonal(t) * Residual(t)

- Formula:

Code Implementation

Here’s how we can put this into practice. Below is a code snippet to retrieve stock market data from August 2019 up to the current date for BBCA. Get ready—we’re about to dive into an exciting journey of exploration and analysis!data variable :

| symbol | date | close | volume | market_cap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBCA.JK | 2019-08-12 | 6040 | 52705000 | NaN |

| BBCA.JK | 2019-08-13 | 6015 | 84406000 | NaN |

| BBCA.JK | 2019-08-14 | 6010 | 81942000 | NaN |

| BBCA.JK | 2019-08-15 | 6000 | 52561500 | NaN |

| BBCA.JK | 2019-08-16 | 5960 | 49821500 | NaN |

seasonal_decompose from statsmodel

seasonal component, we identify the dates where these minimum and maximum values occur. Below is the code snippet to accomplish this:

Explanation:

-

Extract the Seasonal Component: We store the seasonal component from the

seasonal_decomposeresult in a variable calledseasonal. -

Find Min/Max Values: We use

.idxmin()and.idxmax()to get the dates where the seasonal trend reaches its minimum and maximum values, respectively. -

Map Month Numbers to Names: Using Python’s

calendar.month_name, we convert the month numbers of these dates into their corresponding month names. - Display the Results: We print the minimum and maximum period of the seasonal trend, showing the month and day for each.

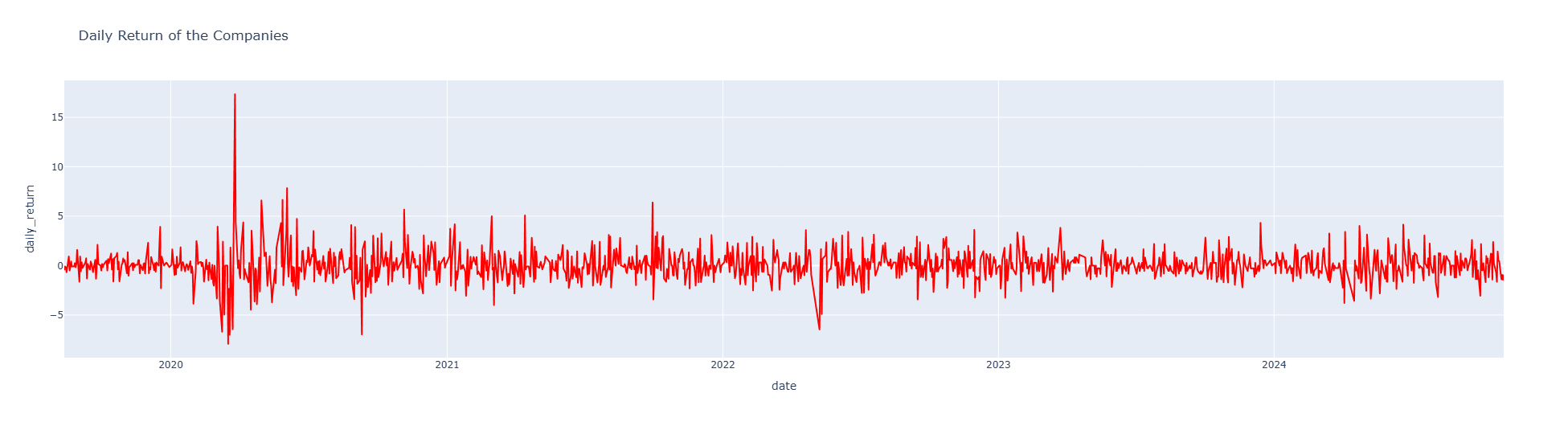

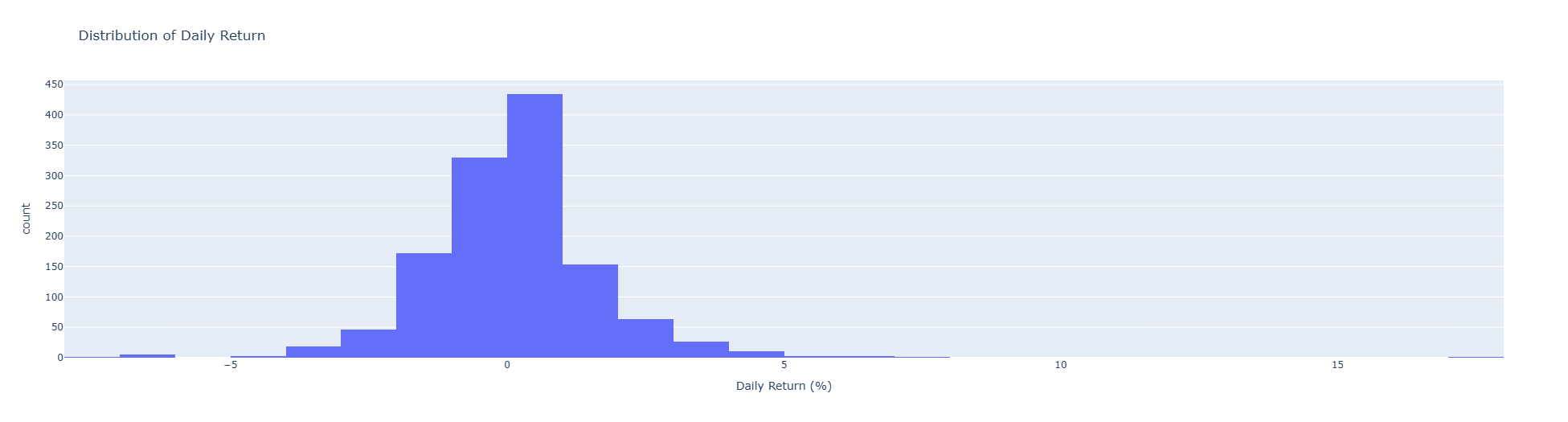

Market Volatility

Market volatility refers to the speed and extent of price changes for a financial instrument over a given time period. High volatility suggests significant price swings, whereas low volatility indicates smaller changes. Common ways to measure volatility include historical volatility and implied volatility, the latter being calculated from options prices. To better understand market volatility, we can analyze the daily returns of the stock as the first step. Daily return represents the percentage change in stock price from one day to the next, which helps in visualizing the frequency and scale of price fluctuations. Using the code below, we calculate daily returns and create a time series plot to observe these variations over time:

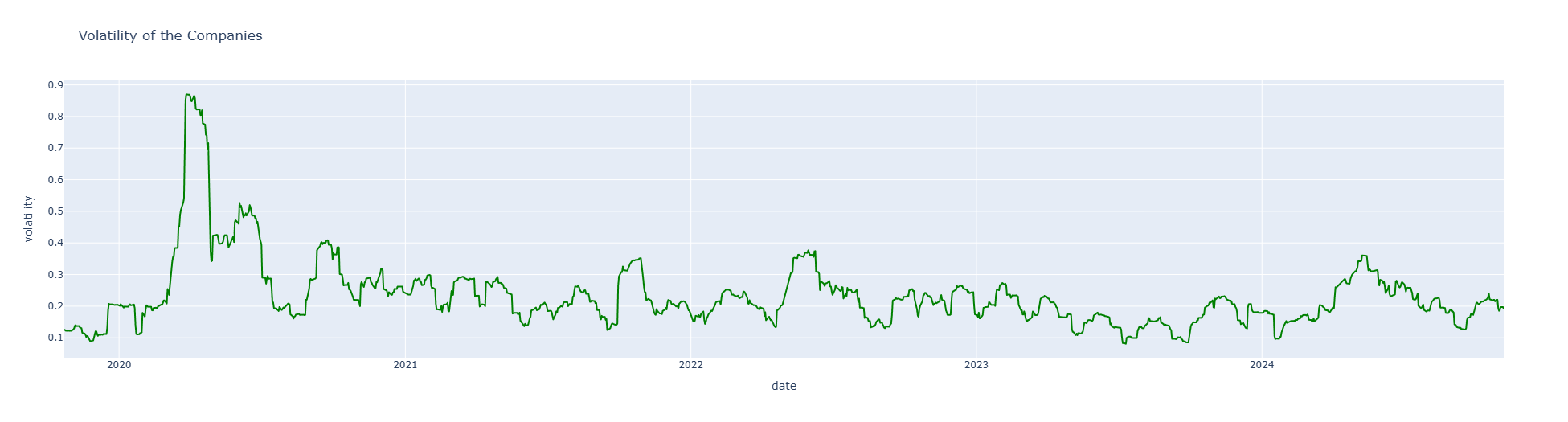

The Annualized Volatility

To gain further insights into market volatility, we can calculate the annualized volatility of the stock. Annualized volatility provides an estimate of the stock’s price fluctuation over a year and helps investors understand long-term risk. Using a 21-day rolling window (approximately one trading month), we compute the daily standard deviation of returns and scale it to an annual measure by multiplying by the square root of 252, the typical number of trading days in a year. The code below demonstrates this calculation and visualization:

Forecasting the Volatility using Machine Learning

After we get the annualized volatility, we could perform the machine learning method in order to forecast the future volatility1. Feature Engineering

In preparation for forecasting volatility, we perform feature engineering to create relevant indicators that capture different aspects of stock behavior. These features provide valuable insights into trends, momentum, and volume, which can influence volatility.- 21-Day Moving Average: A rolling mean over the past 21 days, which smooths price data to highlight longer-term trends.

- Relative Strength Index (RSI): A momentum indicator over a 14-day window that ranges from 0 to 100, indicating overbought or oversold conditions.

- On-Balance Volume (OBV): A volume-based indicator that reflects buying and selling pressure to reveal whether volume is moving in or out of the stock.

- Moving Average Convergence Divergence (MACD): A trend-following measure of the difference between two moving averages, helping detect shifts in price trends.

2. Modeling with Random Forest Regressor

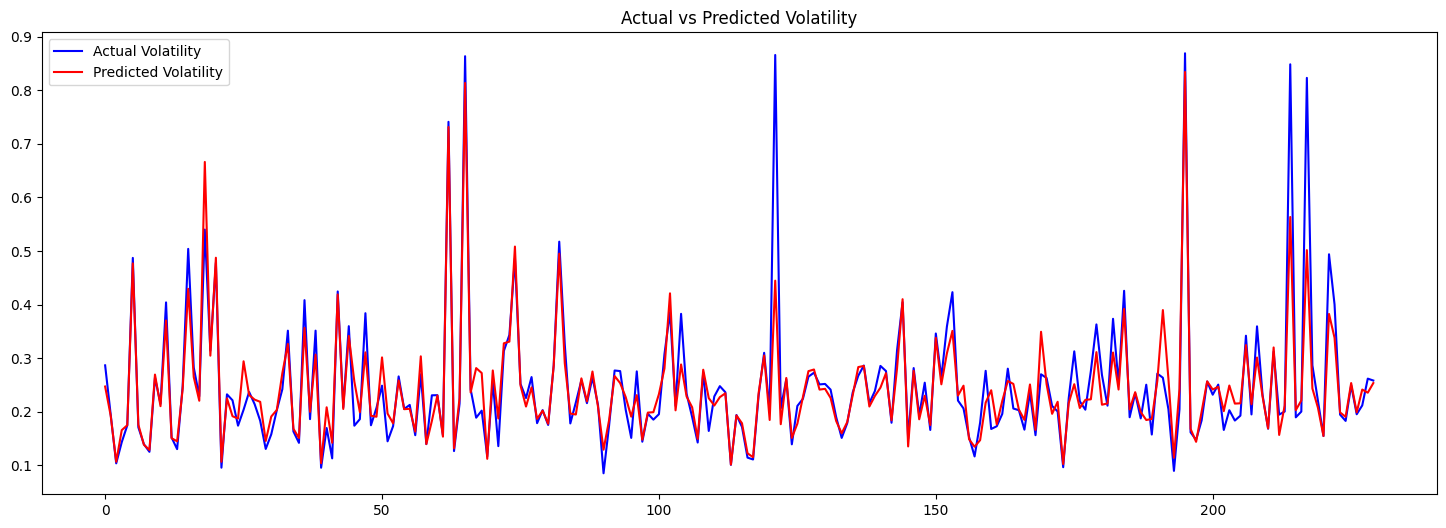

With the features now engineered, we can proceed to building a machine learning model to forecast future volatility. In this example, we use a Random Forest Regressor to predict the stock’s future volatility based on the feature set we’ve created. Random Forests are effective for this type of problem because they handle complex patterns in the data well and are generally robust without requiring extensive parameter tuning. The code below implements this entire pipeline:3. Evaluating the Model

To evaluate the effectiveness of our volatility forecasting model, we can visually compare the actual and predicted volatility values on the test set. This helps us understand how well the model captures the volatility patterns over time. The plot below shows the actual and predicted values side-by-side:

4. Incorporating Volatility Forecasting into a Stock Trading Strategy

To incorporate volatility forecasting into a trading strategy through position sizing, we can use the model’s volatility forecast to adjust the size of our trades. A common approach is to reduce position size when higher volatility is predicted (to minimize risk) and increase position size when volatility is lower. Here’s an example of how this concept can be implemented in Python:

-

Position Sizing Formula: We can use a basic position sizing rule where position size is inversely related to forecasted volatility. For instance:

Position Size = Target Risk / Forecasted VolatilitywhereTarget Riskis a predefined amount of capital at risk per trade. - Setting Up Parameters: We define a risk factor and calculate position sizes based on forecasted volatility.

- Implementation: Below, we calculate position sizes for each day based on the model’s volatility forecast.

- Higher Forecasted Volatility → Smaller position sizes to limit potential losses.

- Lower Forecasted Volatility → Larger position sizes to take advantage of stable market conditions.

| Date | Future Volatility | Position Size |

|---|---|---|

| 2024-08-30 | 0.211042 | 47383.833926 |

| 2024-09-02 | 0.211006 | 47392.010809 |

| 2024-09-03 | 0.208473 | 47967.750053 |

| 2024-09-04 | 0.204720 | 48847.234923 |

| 2024-09-05 | 0.212859 | 46979.355676 |